A childhood in Russia

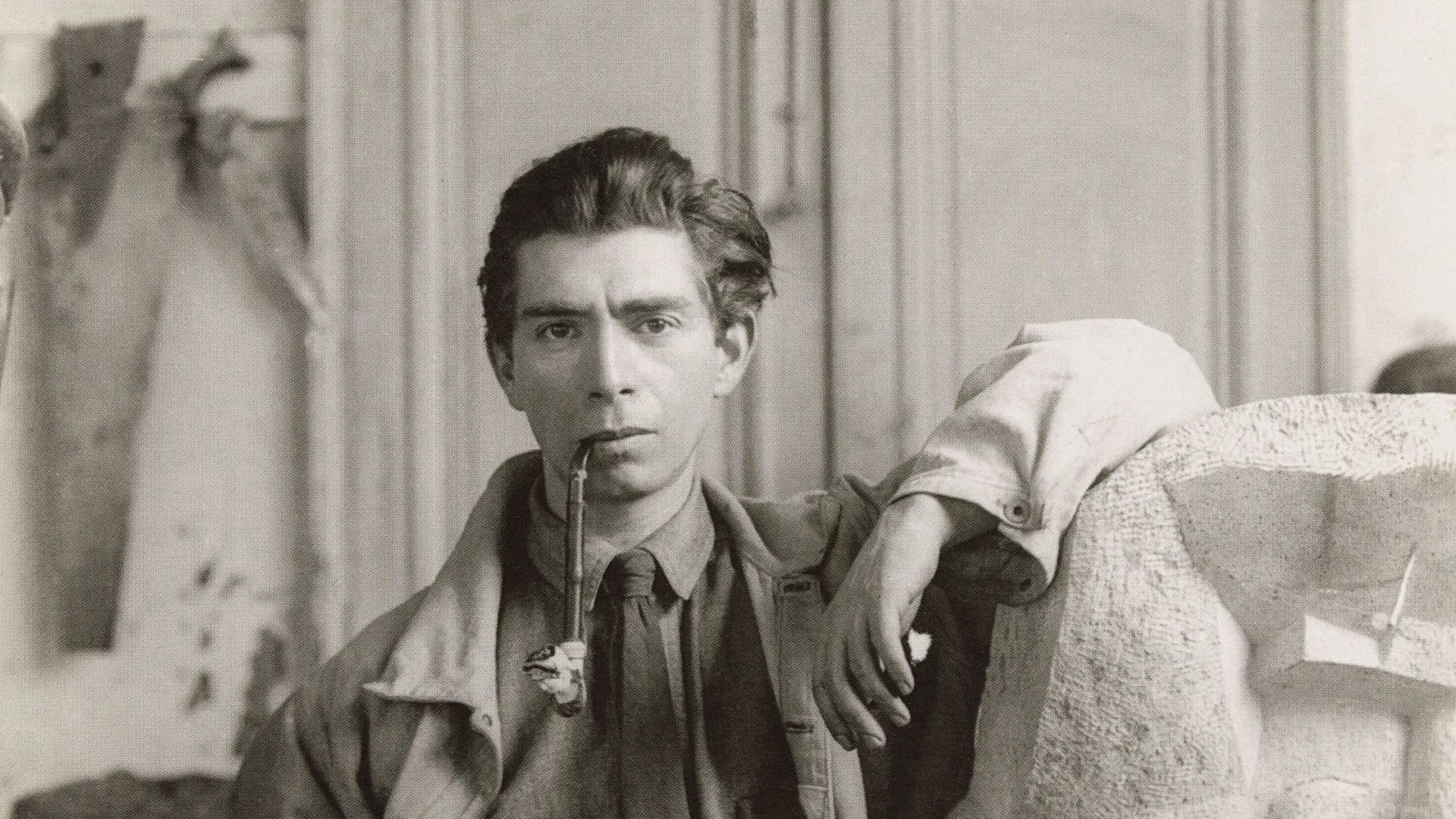

Ossip Zadkine was born on 4th July 1890 in Vitebsk, today in Belarus.

His father, Ephime Zadkine, taught Greek and Latin at the seminary in Smolensk. This man of letters from a Jewish family had converted to the orthodox religion in order to marry Sophie Lester, the descendant of a Scottish family of boat builders, who had emigrated to Russia in the seventeenth century. Brought up “far removed from religious concerns” the young Ossip spent his childhood between the wooden house in Smolensk, the estate of his maternal uncle, on the banks of the Dvina River, and the far depths of the pine forests.

The necessity to “to draw everything at all times” soon made itself felt. The discovery of a block of clay in the garden aroused in the twelve-year-old child a passion for modelling – the first sculpting studio was improvised in a corner of his father's library.

A stay in England

1905-1910 "Go, my child, your path does not lie in these parts"

In 1905 his parents sent him to Sunderland, in the north-east of England, to a certain "Uncle John" who enrolled him in the local art school and introduced him to woodcarving.

In 1906 the teenager joined a friend in London without the agreement of his father who cut off his funds. He enrolled for evening classes at the Regent Street Polytechnic, and spent every Sunday in the British Museum. In order to survive, he worked for furniture craftsmen in the East End - he was given ornaments to carve.

With the benefit of this apprenticeship, he produced his first sculptures using the direct carving method – Head of a Hero in granite, 1908 – during a summer break in Russia. "The prodigal son” had in fact found the way back to the family home and reconciliation. His father made the decision to send him to Paris, "where you can become a sculptor". In the autumn of 1910 Zadkine settled into a hotel in the Latin Quarter.

The Paris debut

1910-1915 Paris where "you can really become an artist"

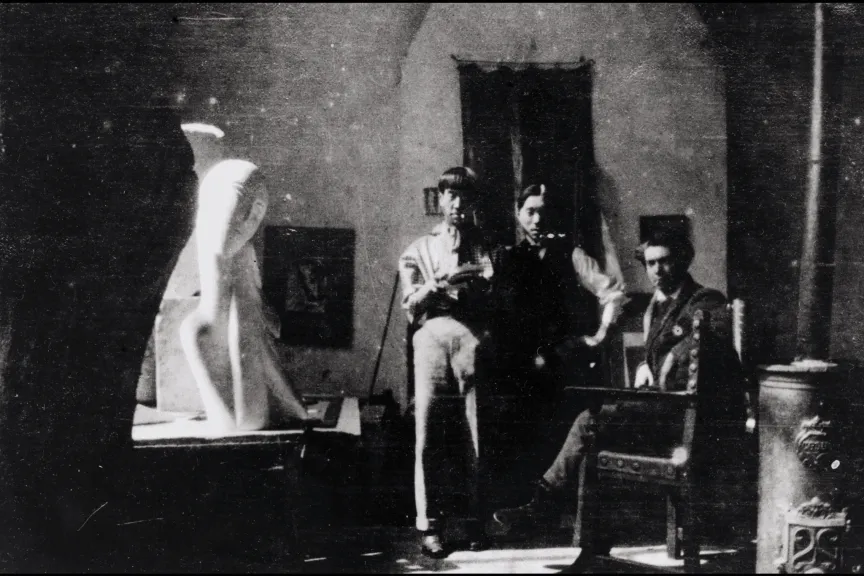

In December 1910, Zadkine enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. After six months, he left. The discovery of Egyptian sculpture in the Louvre and the shock of a Roman head persuaded him to "search for life in the simplification or accentuation" of forms. Like other sculptors of his generation – Amadeo Modigliani, Alexander Archipenko, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska –, Zadkine went back to the living sources of archaism. The only necessity? "To place oneself at the service of the wood” or the stone without putting on “the academic uniform". A manifesto for the technique of direct carving which Zadkine practised from 1911 onwards, hidden away in the “Brie district” in his studio in la Ruche.

In 1912 he moved into 114, Rue de Vaugirard, nearer to the Vavin crossroads and the café of La Rotonde, the magnetic field of modern art. He met Matisse and Picasso, spoke to Apollinaire and shared “the lean times" with Modigliani.

The Salon d’automne of 1913 earned him his first collector, Paul Rodocanachi, who acquired several works including Samson and Delilah and The Holy Family and found him a new larger and sunny studio at 35, rue Rousselet.

The engagement in the First World War

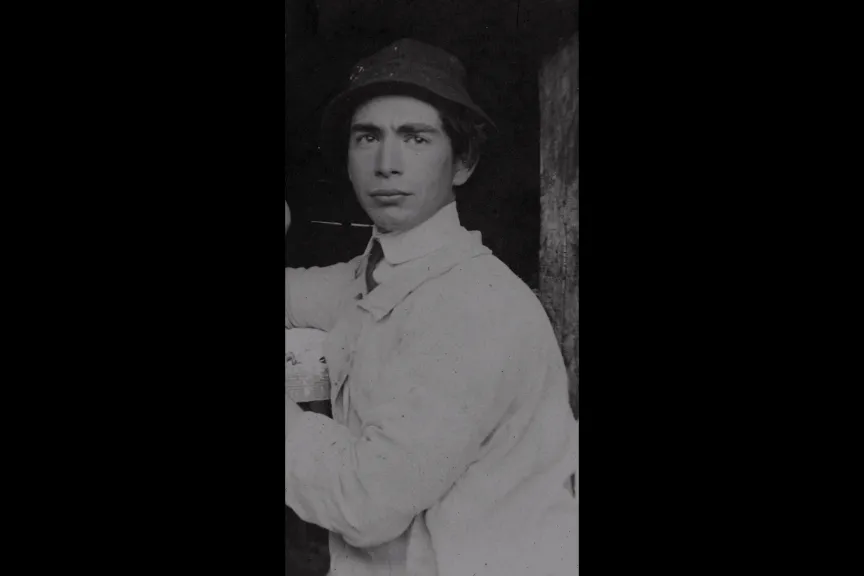

1915-1918 Involvement in the War

On 3rd August 1914, France and Germany declared war. Blaise Cendrars launched an appeal for the mobilisation of "foreigners who were friends of France". On 24th January 1916 Zadkine enlisted voluntarily. He was admitted into the 1st Foreign Regiment, and served in a nurse and stretcher bearer section. In May, he was assigned to the Russian ambulance corps in Champagne: barracks, shells, trenches, evacuation of the wounded, the maimed and hospital wards…

Gassed at the end of November, Zadkine was evacuated and hospitalised in his turn. Decommissioned in October 1917, he returned to the Rue Rousselet with his health in tatters and morale at a low ebb. He brought back forty or so works on paper executed in a hurry – pencil, charcoal, ink and a few watercolours. The strength of expression of these drawings encouraged him to engrave twenty or so which he published in an album under the title Twenty etchings of the war by Ossip Zadkine, a soldier in the 1st Foreign Regiment assigned to the Russian ambulance corps of the French army.

His marriage to Valentine Prax

1918-1920 A Wedding and a Solo Exhibition

His friend the painter Henri Ramey invited him to spend the summer near Montauban, in the mediaeval village of Bruniquel, with which Zadkine found himself in deep harmony – "Doors and windows carved out of stone spoke in a language that appeared to me solemn and beautiful.” In October 1918, he exhibited with Ramey at the Galerie Chappe-Lautier in Toulouse where he presented fifty-seven works on paper and "four directly carved sculptures": one in wood – The Harvest, and three in stone where the hand of the artist was in tune with the shape of the block – Woman with a mandolin. The painter Roger Bissière signed the catalogue.

In 1919 a young painter, Valentine Prax, became his neighbour in the Rue Rousselet.

Both shared exile and the bitter joys of the “bohemian” lifestyle. They married in August 1920 in Bruniquel. Two months earlier, Zadkine had organised his first solo exhibition in his studio: forty-nine sculptures carved out of wood, stone and marble. In the preface to the catalogue, Georges Duthuit highlighted the "bare simplicity" of this creative work.

Cubist interlude and first success

1921-1925 A Cubist Interlude and a First Dedication

In February 1921 Zadkine exhibited at the galerie La Licorne which Dr Girardin had just opened. This same year, he took French nationality and saw his Tigre en bois doré (Tiger in Gilded Wood) and aHead of a Young Girl in marble exhibited at the Musée de Grenoble on the instigation of the curator Andry-Farcy. Research, trial and error and incursions towards “other” forms: in the sculptures produced in 1921 and 1924, Zadkine cut out planes in a more defined fashion, sharpened edges, and submitted the mass to a geometrical rigour. The Woman with a Fan which he exhibited at the Salon d’automne in 1923 and the Accordion Player series are the clearest representatives of the "small, rigid and angular Cubist world" which the sculptor would soon outgrow and return to his own style.

In 1925 the Galerie Barbazanges, one of the first in Paris, devoted a large exhibition to him. The critic Waldemar-George reported the "Barbarous and primitive idols” of Ossip Zadkine – "This Slav who revives myths is a poet who dispenses emotion of a mystical and religious order". (L’Amour de l’art)

The Greek source, the entrenchment of a "land"

1926-1941 The Greek Source, Putting Down Roots in the "Land"

His work underwent profound changes. Without abandoning direct carving, Zadkine produced models in plaster or clay which were then cast in bronze. The Maenads, Birth of Venus,Draped Figure, Orpheus Walking and Diana … Freed from the restrictions of the compact block, the shapes yield to the harmony of a fluid rhythm. His journey in Greece (1931) confirmed this return to the “crystal clear springs of the religious and aesthetic philosophies" of ancient art.

In 1928 Zadkine had left the studio in the Rue Rousselet for the "oasis" of the Rue d'Assas. His reputation was consolidated by solo exhibitions in London (1928), at the Venice Biennale (1932), at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels and in New York (1933). But due to the effects of the economic crisis, collectors vanished.

Faithful to the Pays du Quercy which he had discovered in the summer of 1918, Zadkine and his wife found their "land" in the village of Arques – a large dilapidated house with a barn which they moved into in 1934.

A land from which Zadkine had to tear himself away after the defeat of France and the stranglehold of the Nazis. At the end of May 1941, he obtained a visa for the United States.

Exile in New York in 1941

Zadkine embarked in Lisbon on 20th June 1941 on the Excalibur, the last American ship to leave Europe. In New York, he rented a studio in the Greenwich Village district: everything had to be improvised and started from scratch, "but his heart was not in sculpting. The news I received from France was too bad." And letters from Valentine were too rare, isolated, harassed and "stupefied" by the forces of destruction.

However in October 1941, Zadkine exhibited at the Galerie Wildenstein, gouaches for the main part. In March 1942, the Galerie Pierre Matisse invited him to take part in the exhibition "Artists in Exile" along with Léger, Chagall and Lipchitz …

Zadkine also worked as a teacher, particularly at the Art Students League.

Reading the book by Mario Meunier La légende dorée des dieux et des héros (The Golden Legend of Gods and Heroes)inspired him to create a series of drawings on The Labours of Hercules – heroic combat was a topical event and was expressed through the artistic and poetic symbolism of The Prisoner (1943) and Phoenix (1944), two remarkable sculptures from this period.

On 5th September 1945 Zadkine obtained his visa, and on the 28th September he disembarked at Le Havre.

Start building again

1945-1958 : “Beginning to Rebuild"

Zadkine returned to France "greatly changed and devastated" but resumed life in Quercy. "First of all I made a group of three characters the base of which was like the aftermath of a disaster – broken forms, chaotic in their decline – and the top pierced but rebuilt; I was facing The Human Forest". Amidst the chaos his art regained a unity of movement and momentum. The memory of the towns shattered by the war – Le Havre, Rotterdam – dictated to him the project for the monument of The Destroyed City “with its arms thrown up towards the sky”. The municipality of Rotterdam ordered this monument from him in 1950.

In the same year, Zadkine received the grand prix for sculpture at the Venice Biennale and took part in the exhibition “L’Art sacré, œuvres françaises des XIXe et XXe siècles” (Sacred Art, French Works of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries) at the Musée National d’Art Moderne. The first work in wood which he carved on his return with "an intense and intimate joy" was a Christ, acquired by the State in 1952. He continued to teach in his Paris studio and at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. International recognition was displayed through exhibitions at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels (1948), the Boymans Museum in Rotterdam (1949), and the Fujikawa Gallery in Japan (1954).

New ways

1959-1967 : Decidedly Unexplored Pathways

Zadkine was now one of the great names of 20th-century sculpture – the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne (1960), the Tate Gallery in London (1961), and the Kunsthaus in Zurich (1965) devoted large retrospectives to him. Despite his precarious health, he lived in a perpetual “state of searching", mobilising his forces for projects and the production of monumental works – that of the The Human Forest (1960-1962) erected in front of the headquarters of the Van Leer Foundation in Jerusalem and that of The Dwelling (1963-1964) for the Nederlandsche Bank in Amsterdam.

In 1962 he began to write his memoirs, published under the title Le maillet et le ciseau, souvenirs de ma vie (The Mallet and the Chisel, Memories of my Life).Concerned about the future of his works, he dreamed with Valentine of opening a museum. The first annotated catalogue of his sculptures appeared in the monograph devoted to him by Lonel Jianou in 1964. Around 1965 he set off down the unexplored and mysterious pathways of "sculptures for architecture, “which he dreamed of deploying on a grand scale in urban spaces.

On 8th November 1967 he completed the bust of his friend the writer Claude Aveline. He died on 25th November in the morning. He is buried in the cemetery of Montparnasse.

“But it is in any case very beautiful to end your life with a chisel and mallet in your hands." (Zadkine, Diary, October 1966).

All quotations, except where otherwise mentioned, are extracts from Zadkine's book LE MAILLET ET LE CISEAU– Souvenirs de ma vie. [THE MALLETT AND THE CHISEL - Memories of my life].